It's not rocket science, it's building science

104,999,999 HVAC electrifications to go and lessons learned

The process to electrify our 1400 sf cabin makes it clear how hard it is going to be to electrify 105 million homes - and where many of the opportunities are. What lessons can we learn that will make the next few million easier and faster? The first lesson is about how the building science works. It’s not rocket science, but it’s definitely science….

There are three big stages for an HVAC refit.

Step 1 - Measure the leakiness

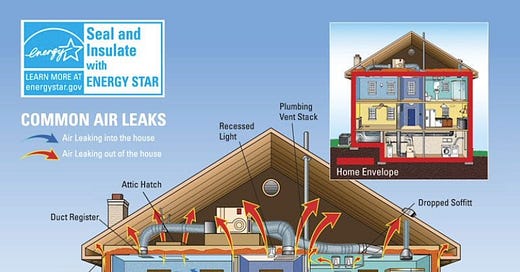

The very first step is to measure the leakiness of your house. What’s leakiness? It’s any place air can escape what professionals call the building envelope, but you can think of it as the walls and windows of the house. If your house leaks a lot, it’s like trying to heat it with the windows open. You might eventually be able to make it warmer, but it’s going to require a much bigger furnace and much more energy than if all the windows were closed and airtight. The leakiness of the house is the single biggest factor in sizing an HVAC unit - and why so many houses have oversized furnaces. Sealing the house also helps counteract the “stack effect” which happens when the hot air in your house rises. Rising warm air increases the pressure in the upper floors (making more hot air escape) while the resulting vacuum simultaneously draws colder air into the lower floors - which means heating new air all over again.

Testing the leakiness requires a door blower test, which is exactly what it sounds like. A technician attaches an airtight fan to the front door of the house to suck (or blow in some cases) air out of the house. The test, which takes about 20 minutes and uses equipment that costs about $4000, can measure the pressure it creates and the amount of air that’s escaping. The goal is to get the leakage rate down to a one-to-one ratio between the amount of air escaping (as measured by cubic feet per minute) and the square footage of the house.

Here’s a specific example. When Dave Barnes, an HVAC and home comfort expert (my description of his job), did a door blower test on our 1400 square foot Markleeville cabin, he measured 2085 cubic feet per minute of leakage for a ratio of 1.5:1. Dave then used a thermal imaging camera to see where cold air was coming in from the outside. The biggest culprits were leaks around our HVAC vents, ceiling lights, switchplates, outlets, and all of our doors (or exactly where the Department of Energy’s diagram said it would leak). After several hours of work with duct tape and spray foam, he managed to reduce the leakage rate to 1555 CFM. So a 25% reduction with duct tape and spray foam. This translates to a 25% reduction in heating requirements. That’s not adding insulation or replacing windows - just duct tape and spray foam. He thinks that with a little more sealing work we could easily get down to 1000 ft.³ per minute. So this first step is actually several smaller steps - the very first blower test, sealing the house, and then doing another blower test to get a final number.

Step 2 - Sizing the system

Once you have the measurement of how leaky the house is, HVAC technicians plug that number plus a whole bunch of others into software to size the system. There are many different platforms, but they all take into account the leakiness of the house, the house location, the number of rooms, the number and size of windows, the orientation of the house to the sun and so forth to come up with a number of BTUs necessary to heat and cool the house. These calculations are complicated (addressable with rules and processes), but not complex (lots of unknowns). To use the example of my home again, Dave’s recommendation is that if we can get down to 1,000 cubic feet per minute leak level, which would be a .71:1 ratio, we could use a 24,000 BTU heat pump for both heating and air conditioning. To put this into perspective, our current furnace generates 88,000 BTUs. That HUGE difference translates into purchase price savings and energy savings for me on my electrification journey.

Step 3 - Designing the system.

In the very last step, an HVAC designer will design a system based on the unique characteristics of the house to balance the cost of installation and efficiency to create a comfortable home. To go back to my home, one possible solution is to use a mini-split ductless heat pump with three air handlers - one for the common area and one for each of the two bedrooms. But we happen to have adequate ducting already installed in a mostly climate-controlled crawlspace (ducts won’t lose much heat to the surrounding air), so the best solution is simply to swap out our propane-powered furnace with an electric heat pump. We are also going to add resistance electric heat strips for extremely cold days (it gets down to single digits).

This is part of what we need to do for houses across the country. I say “part’ because there are other components to electrification. But HVAC seems to be the biggest single dollar number - and likely the contractor who will get calls in the middle of the night. You won’t be calling your insulation installer because it’s no longer working.

But as you can see from the many manual inputs in the process and the picture of one of the software packages available, there are lots of areas to be improved. More on that next week.

Resources

The best resource that I found is Nate “The House Whisperer” Adams’ book called The Home Comfort book. It describes everything you'll ever need to know about HVAC. The book is full of illustrations, informative and actually really entertaining. Nate also has two YouTube channels covering similar material here: Check out the House Whisperer and HVAC 2.0.

Cool Happenings:

Lun raised 10.3m Euros to help tradespeople with the entire process of installing heat pumps. According to TechCrunch, “Its software aims to take some of the strain out of installation assessments, design, and planning, as well as handle other business elements like taking payments. It’s providing tradespeople with a suite of tools for gathering relevant data from householders and automating suitability assessments — doing the latter by drawing on public and/or open data (such as satellite imagery), as well as feeding in data from OEMs (such as price, specifications), as well as property type/location etc, to try to find the best match between a job and a professional installer.” Definitely sounds like a step in the right direction - especially if they solve some of the issues described above.

This isn’t new, but I just found it - the Ephoca AIO (All-in-One) heat pump combines the compressor and the air handler so that there isn’t an outside unit required. It only needs two vents to get to the outside air. It’s perfect for small apartments and studios. Seriously cool.

Heat pumps are already ubiquitous in Asia. When will the US catch up? - Canary Media’s @JulianSpector writes about how heat pumps are so ubiquitous all over Asia that they just blend into the landscape. Only in the US are they so hard to find.

Love the grabbiness of that subheader.

104999999 to do. It really pushes the point of the challenge ... and the opportunity